“Richer than the Stroganovs you’ll never be.”

The longevity and importance of the Stroganov dynasty is integral to the history of Russia. They remained a wealthy and powerful family from the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the sixteenth century to the Russian Revolution in 1917. Initially they made their vast fortune by manufacturing salt. Their financial support of the government of Peter the Great was rewarded with the family being elevated into the Russian aristocracy. For generations the Stroganovs served Catherine the Great and other Russian rulers as advisers and confidants.

In the sixteenth century, their grand estate in Perm marked the eastern border of Russia, and it remains the gateway to Siberia today. Their dominance of this eastern frontier, where numerous Sasanian silver vessels have been discovered, enabled the Stroganovs to amass vast quantities of antique silver and to become the first modern collectors of Sasanian metalwork. Known as world-class art collectors, they also acquired extensive holdings of Russian icons, European Old Master paintings, and even pre-Columbian art.

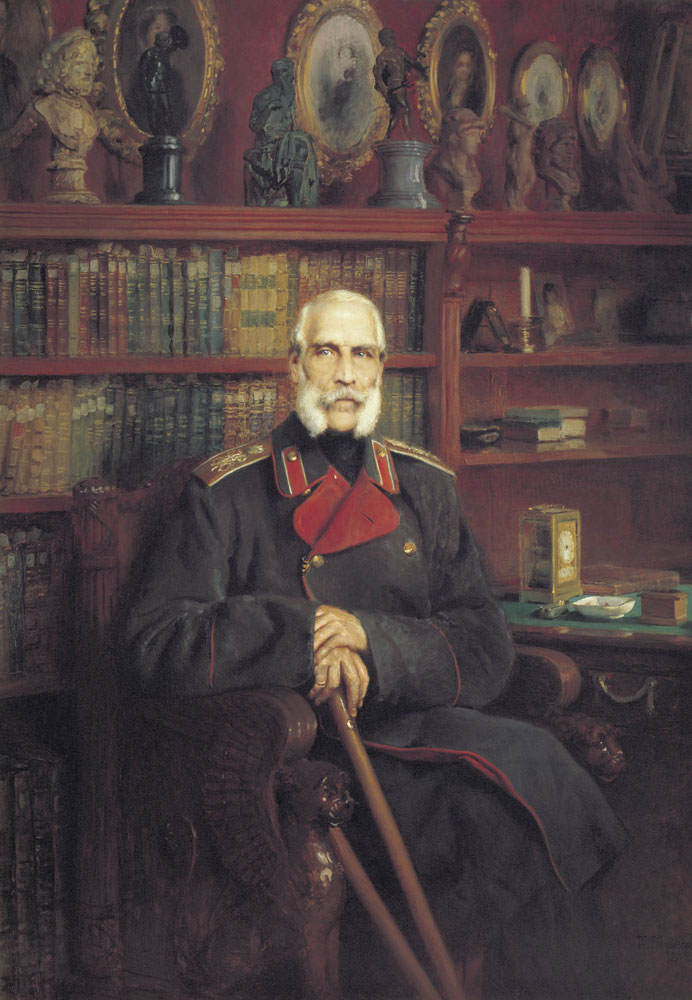

Alexander Stroganov (1733–1811) was such a renowned art connoisseur that even Catherine the Great was said to be envious of his collection. When a silver Sasanian ewer was found on his estate in Perm, he sent it to Paris for further study, thus pioneering interest in ancient Iranian metalwork. Count Sergei Grigorievich Stroganov (1794–1882), the most archaeologically and artistically inclined member of the family, was a founder of the Imperial Archaeological Commission in 1859, and he conducted excavations on his estates. Through purchases and excavations, he amassed a large collection of Sasanian vessels in the 1870s, including the Shapur plate, which became known as the “Stroganov” plate. It was displayed at the Stroganov Palace in Saint Petersburg and was widely published in Russia.

Thanks to the Stroganov family’s early interest in Sasanian metalwork, Russia continues to have the most important collection of Sasanian metalwork outside of Iran today. While much of the collection is in the Hermitage, Sasanian metalwork can be found in museums throughout Russia.

Beef Stroganoff

Recipes for beef stroganoff appeared in Russian cookbooks in the mid-nineteenth century, even though similar dishes had long been enjoyed in Russia. The Stroganov name became associated with this beef dish through Count Pavel Stroganov, a dignitary in the court of Alexander III and a gourmet who loved to entertain. His chef refined the recipe and submitted it to a culinary competition in 1891. (In Russia, dishes were often named after the noble family who employed the chef, rather than after the chef himself.) Variations of the recipe became popular throughout Russia and China, and soon spread around the world.

Elena Molokhovet’s Original Beef Stroganoff Recipe 1861

Govjadina po-strogonovski, s gorchitseju

Two hours before serving, cut a tender piece of raw beef into small cubes and sprinkle with salt and some allspice. Before dinner, mix together 1⁄16 lb (polos’mushka) butter and 1 spoon flour, fry lightly, and dilute with 2 glasses bouillon, 1 teaspoon of prepared Sareptskaja mustard, and a little pepper. Mix, bring to a boil, and strain. Add 2 tablespoons very fresh sour cream before serving. Then fry the beef in butter, add it to the sauce, bring once to a boil, and serve.

Ingredients

2 lbs tender beef

10-15 allspice

1⁄4 lb butter

Salt

2 spoons flour

2 tablespoons sour cream

1 teaspoon Sareptskaja mustard

Recipe translation from Joyce Toomre, ed., Classic Russian Cooking: Elena Molokhovets’ A Gift to Young Housewives (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1998), 213–14.

“I beg of you to instruct someone to draw from every side the silver vessel that was found in the earth in Perm. . . .” Alexander Stroganov wrote to his father in 1753 after this Sasanian silver ewer was found on the family’s estate in Perm. He later transported the ewer to Paris for further study. It was unfortunately lost during the French Revolution.

Count Sergei Stroganov not only amassed a large collection of Sasanian metalwork, but he also encouraged archaeological research in Russia. Due to his early efforts, Russia remains a center of research on ancient Iran.