How did an important Sasanian hunting plate travel from Iran to the border of Siberia? Numerous Sasanian vessels have been unearthed in northeastern Russia, a fact that continues to puzzle scholars. Towards the end of the Sasanian Empire in the seventh century, the Shapur plate was probably seized by marauding tribes from the Caucuses. At that time, the empire was in rapid decline and fighting a bitter war with the Byzantines, who were centered in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). The Byzantines offered gold and silver vessels and many other treasures to the Khazar tribesmen of the Cancuses as bribes to raid Iran. A path of discoveries of silver vessels out of Iran suggests tribes carried their loot north to trade with the Russians.

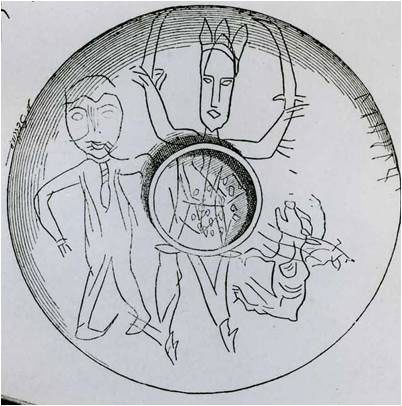

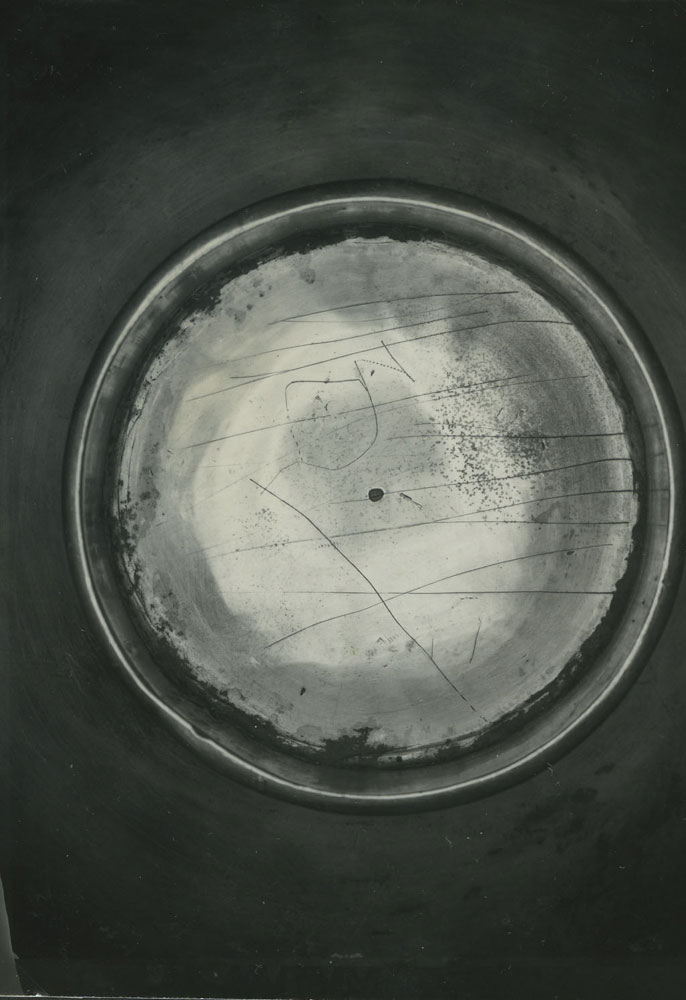

Northern Finno-Ugrian tribes in the Perm region of Russia probably traded the Shapur hunting plate for furs. They scratched human and animal forms as well as abstract designs into many vessels, perhaps as a way to incorporate the Sasanian objects into their own rituals. The foot of the Shapur plate has several scratches that were likely added in Russia. The Finno-Ugrians might have buried their silver vessels to avoid paying taxes to the Russian tsars. The piles of coins stashed with them help to date when they were buried. Many of these ancient Sasanian objects have been preserved for decades, deep in the Siberian frontier.

Sasanian vessels have also been found in China, Central Asia, Europe, and Armenia as well as Iran and Russia. A Sasanian plate in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France is known to have been in Paris since the thirteenth century. This suggests Sasanian metalwork was highly valued and traded in medieval Europe.

The graffiti (an art historical term that refers to added incised lines, not vandalism) on this plate was most likely made by Russian tribes who traded with ancient Iranians for furs. Such imagery suggests the plate was used in an elaborate ritual.

The scratches on the foot of the Shapur plate resemble those on other Sasanian vessels found in Russia. This suggests that, like those objects, this plate might have been used in ancient rituals.

The Russian archaeologist Ya. I. Smirnov catalogued every known piece of “eastern silver” in Western collections in 1909 (indicated by red dots). The dotted square is the Perm region where the Shapur plate was discovered.

Ya. I. Smirnov with modern adaptations and translation; From Ya. I. Smirnov, Vostochnoe serebro (St. Petersburg, 1909)