His writing conquered the world and is among other writings as the sun among other planets.

—Qazi Ahmad, Gulistan-i honar, circa 1595

Later honored with the titles of “sultan of calligraphers” and “cynosure of calligraphers,” Sultan Ali Mashhadi enjoyed a long career before he died in 1520. He spent many years in Herat at the court of the Timurid princes Abu Sa’id (reigned 1458–69) and Sultan Husayn Mirza (reigned 1469–1506). Active in the library-workshop (kitabkhana), Sultan Ali also trained dozens of pupils in the art of calligraphy, many of whom became illustrious practitioners working in princely ateliers.

A native of Mashhad, Sultan Ali retired in 1510 in his hometown in northeastern Iran. Four years later he composed the Sirat al-sutur (The path of writing), an epistle in rhymed verse in which he draws a parallel between calligraphic practice and religious discipline.

On a technical level, Sultan Ali Mashhadi defined new rules for nasta‘liq and elevated the script to its classical form. The historian Khwandamir, who died in 1534, asserted Sultan Ali “obliterated the calligraphy of masters of the past and present.” Writing around 1600, the Persian author Qazi Ahmad claimed Sultan Ali’s handwriting “attained such a degree of perfection that is seems incredible anyone could emulate him.”

Nasta‘liq developed into a perfect vehicle to pen Persian prose and poetry. It was employed to transcribe works in Turkish, but it was seldom used to copy texts in Arabic. These two folios come from a collection of poetry (divan) written by Sultan Husayn, the Timurid ruler of Herat from 1469 to 1506. The poems in this now-dispersed manuscript are composed in Chaghatay, an eastern Turkic dialect.

The four lines of verse (quatrains) were executed in découpé calligraphy (qat‘), a virtuoso technique that was probably developed in the Timurid court workshop at a time when Sultan Ali Mashhadi was active there. Dots, letters, and syllables in light tones have been cut out and pasted onto a darker contrasting background, creating a dazzling effect. No trace of the collage process is visible even on close inspection. This dexterous cut-out work has been attributed to Shaykh Abdallah Haravi, a master of the genre.

Nevertheless, the script here, with its subtle balance between elongated and compressed strokes and the variation in thickness, points to the style of Sultan Ali Mashhadi.

Attributed to Sultan Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520)

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, Timurid period, ca. 1490

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Purchase

Freer Gallery of Art F1929.66 and F1929.67

Sultan Ali Mashhadi signed his calligraphy in the lower triangular corner. Instead of including the traditional term katabahu, a term that indicates a sense of achievement, he used mashaqahu, which suggests it was a “work in progress,” a practice piece or an instruction exercise that one of his numerous students could study and try to replicate.

Such calligraphic fragments were often mounted onto album pages at a later time. These particular verses were clearly deemed worthy of preservation because they were copied by the most celebrated calligrapher of the late Timurid period (circa 1470–1506). As is almost always the case with album pages, the aesthetic relationship between text and image dominates. The content of the quatrain does not relate to the verses displayed on the borders or to the figures later painted by the illustrious Safavid artists Muhammad Sadiqi and Muhammad Qasim, who were both active around 1600.

Signed by Sultan Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520)

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, or Iran, Mashhad, Safavid period, ca. 1510–15

Paintings ascribed to Muhammad Sadiqi and Muhammad Qasim

Iran, probably Qazvin, Safavid period, ca. 1590

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler S1986.30

This elaborate folio presents four calligraphic panels (clockwise from upper left): two unsigned couplets; three couplets copied by Sultan Mahmud; two couplets by Shah Muhammad; and two couplets by Sultan Muhammad Nur. Writing in gold in the triangle above his work, Sultan Muhammad Nur states he penned this example by imitating the style of “Mawlana [our master] Sultan Ali al-Mashhadi.” The unsigned couplets in the upper left corner could well be the work of Sultan Ali Mashhadi. Its carefully modulated line and the visual balance between fluid and disciplined strokes are indeed distinctive of his work. Also, combining Sultan Ali Mashhadi’s calligraphy with examples by three of his outstanding students on a single page underscores the fundamental importance of the master-pupil relationship.

Signed by Sultan Mahmud, Shah Muhammad, and Sultan Muhammad Nur

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat and Ahmedabad, Safavid period, 16th century

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler S1986.349

Compared to the calligraphy of Mir Ali Tabrizi, the nasta‘liq script of Sultan Ali Mashhadi introduces a different visual rhythm. Words above the baseline, for example, are executed in a steeper pitch. Variations in the width of strokes further emphasize how the master calligrapher controlled and modulated the script in a spacious, even delicate manner. These characteristics, which are evident in this copy completed early in Sultan Ali’s career, become more accentuated in his later works and in his examples of large nasta‘liq script.

Signed by Sultan Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520)

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, Timurid period, dated 1468 (873 AH)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Gift of the Art and History Trust in honor of Ezzat-Malek Soudavar

Freer Gallery of Art F1998.5 folios 44v–45r

To increase the prestige of their libraries, later Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman connoisseurs collected manuscripts that had been copied in nasta‘liq by master calligraphers. Chief among them were works by Sultan Ali Mashhadi. Not only was he one of the most illustrious calligraphers of his day, but he was also closely associated with the Timurid court, which set the standard for cultural sophistication for later rulers. This copy of the Gulistan (Rose garden), an anthology of poems by the Persian poet Sa‘di (died 1292), is acknowledged as one of the finest manuscripts Sultan Ali Mashhadi ever produced.

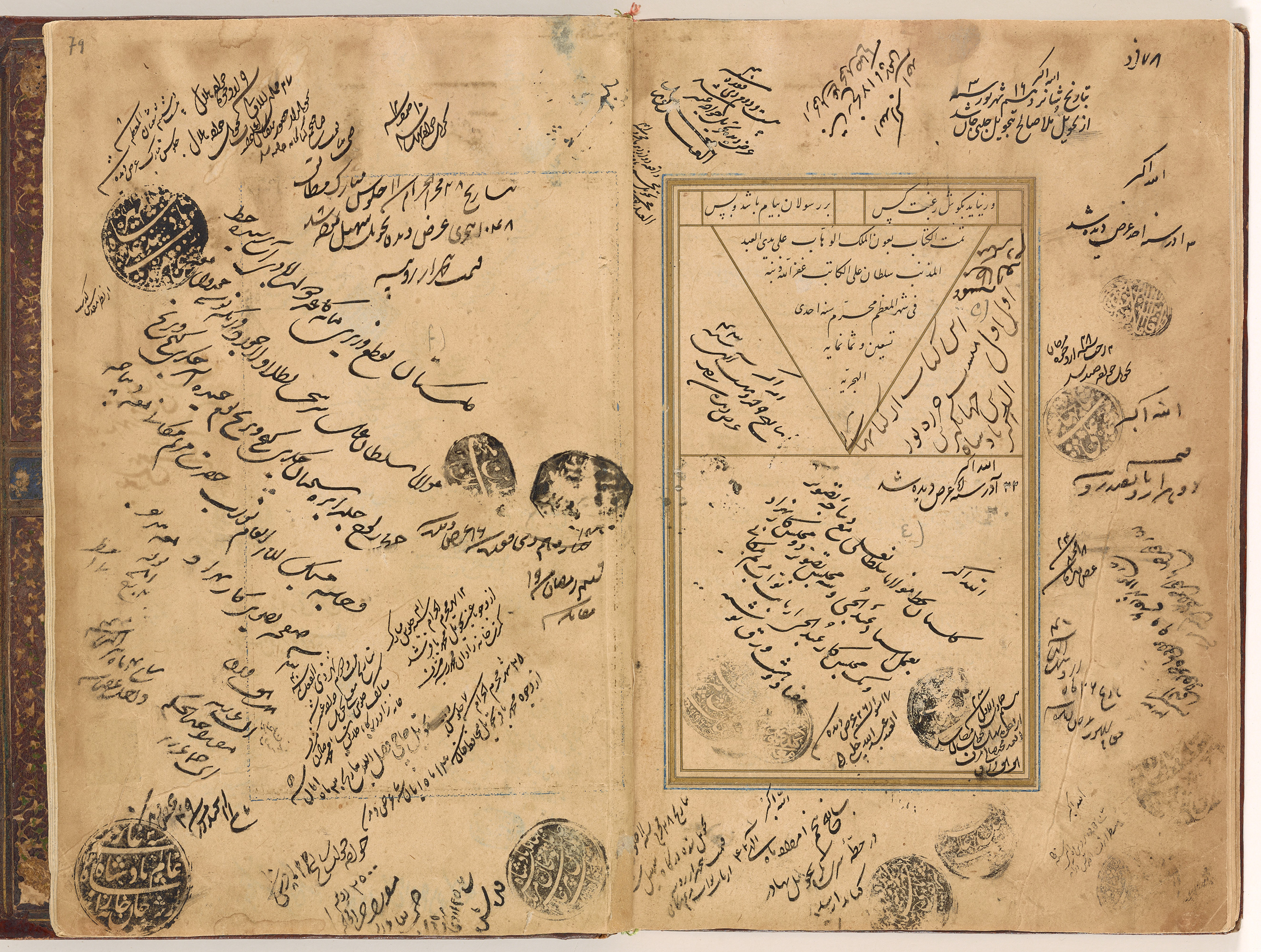

The calligrapher’s carefully penned signature appears in the triangular colophon. Later owners and librarians added their names and comments, more or less elegantly, in various styles of nasta‘liq. One somewhat clumsy example is located to the right of the triangle. Written by the Mughal ruler Jahangir (reigned 1605–27), the inscription maintains: “This is one of my earliest books. I read it constantly. Written by Nur al-Din Jahangir, son of King Akbar.”

Signed by Sultan Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520)

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, Timurid period, dated 1486 (891 AH)

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.30 folios 78v–79r

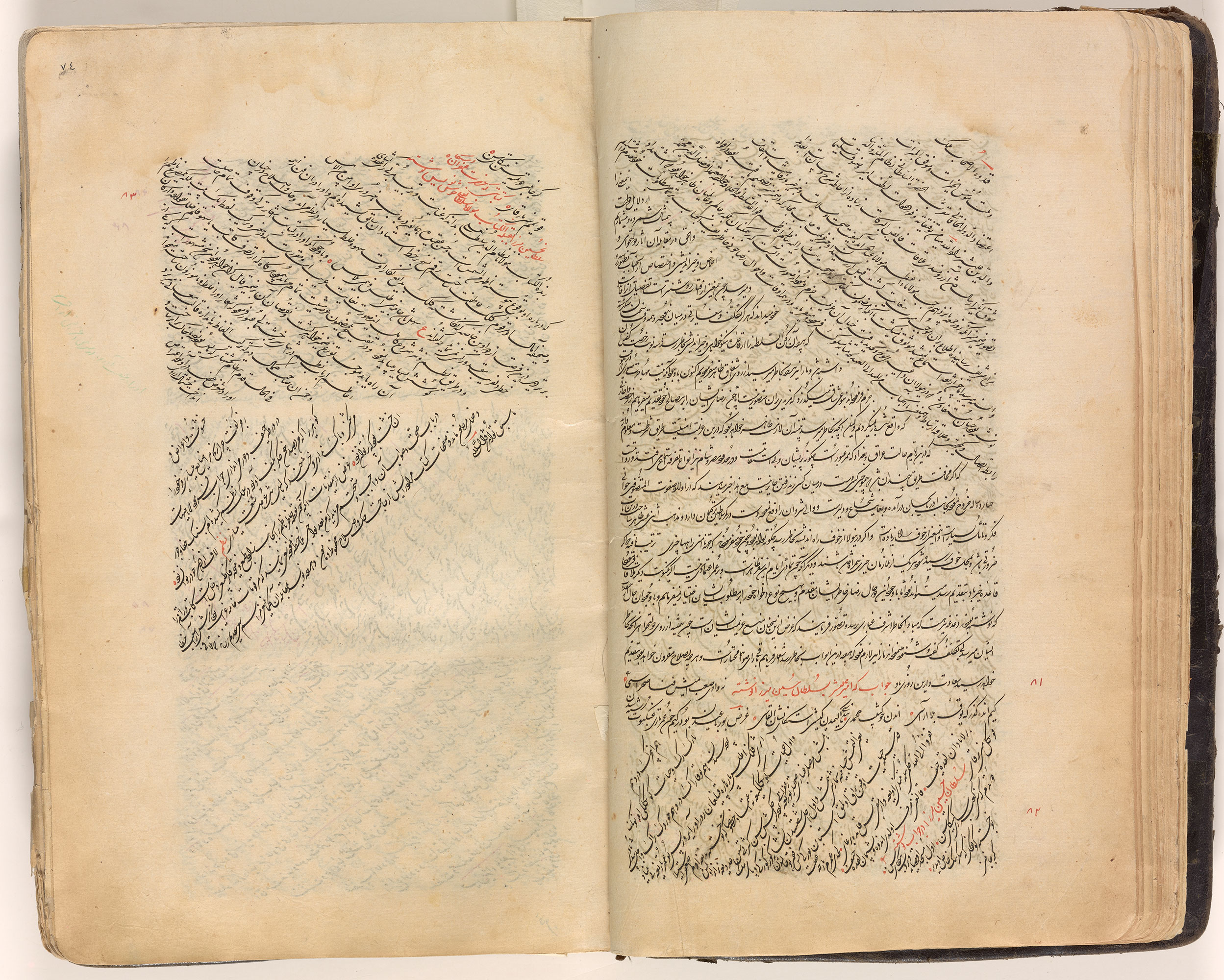

Ivughli, a secretary (munshi) at the Safavid court, compiled this collection of correspondence (majmu‘a-i munsh’at) sent by Persian rulers, from the Great Seljuks in the eleventh century to the Safavid shah Safi I (reigned 1629–42). In Iran, the art of letter writing was as much esteemed as eloquence and rhetoric. Penned in neat shikasta nasta‘liq (“broken nasta‘liq”), the text alternates between paragraphs written horizontally and diagonally from the right or the left.

One letter of particular interest is on the left-hand page. Composed by the Timurid ruler Sultan Husayn (reigned 1469–1506), it is addressed to the celebrated calligrapher Sultan Ali Mashhadi (died 1520). The sovereign reprimands the calligrapher for making too many mistakes when copying poems written in Turkish, the language Sultan Husayn used for his own poetry.

The letter reads:

May the best of scribes, Master Nizamuddin Sultan-Ali, realize that the favor and patronage of the patron’s all-solving mind that have attached to him are more apparent than the sun, and the royal good opinion of his art is more obvious than yesterday. We have written the page of his hopes with the pen of affection, drawn the pen of abrogation through the calligraphy of former masters, and consider him above all others in that art. However, in the royal divans that have been scriven by his miraculous pen, many mistakes and errors are to be seen, and scratching and corrections in such enchanting calligraphy are unforgivable, as has been said:

Clothing half of brocade and half of sackcloth is worthless.

In view of the fact that he has acquired a perfect expertise in the copying of Turkish poetry and has a great mastery of the manner of poetry and prose, this is abundantly strange. It is well known that in the meaning and layout of the words of a line of poetry—not to mention a hemistich—the composer must make a great effort, and to perfect a conceit he must make a great exertion of will power. When error creeps into the rules and regulations through scribal intervention or a slip of the pen, it causes displeasure, and the defect lies heavy on the mind of the poet.

The story is well known that while out for a stroll a great poet passed by a brickmaker reciting the poet’s poetry—but it was recited erroneously and uncadenced. When the master poet saw the arrangement of his words was being poured badly into the mold of meaning, he immediately stepped onto the bricks the man had made and crushed them into the dust. The brickmaker said in anger, “Why have you wasted my efforts and indulged in such cruelty?”

“Oh,” he replied, “you crush with the stone of cruelty a pearl that cost me so much effort to string onto a line of poetry, and you think nothing of it? Yet you turn the few bricks you have fashioned into an excuse to be rude and impolite.”

One can spout nonsense from the mouth like pearls: it is a brick that can break a wing.

The point of these preliminaries is that since there is a natural connection between the poet’s mind and the product of his poetic nature and contemplation, scribes and copyists must take great pains to be correct and free of error, and henceforth you will pay attention and strive to ensure that what is written by your miraculous pen is protected from the calamity of error and mistake, and the pages free of any necessity to scratch out and make corrections. You must endeavor appropriately in all that you write in order to receive as before. Peace.

Translation excerpted from Wheeler M. Thackston, Album Prefaces and Other Documents on the History of Calligraphers and Painters. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill, 2001, p. 51.

Iran, Isfahan, Safavid period, dated 1682 (1094 AH)

Ink and color on paper

Gift of Nader and Narges Ahari in memory of Nasser Ahari

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S2014.7