Calligraphy Implements | Before Nasta’liq | Khafi and Jali

Calligraphy, or “beautiful writing,” has long been acknowledged as one of the most revered artistic achievements of the Islamic world. Calligraphy originally evolved to give visual form to the Koran, the word of God as transmitted to the Prophet Muhammad. From the eleventh century onward, this endeavor led to the creation of a series of codified scripts in the Arabic alphabet used to pen both religious and secular texts. In Iran, a land with its own rich literary tradition, these scripts were employed both for writing in Arabic and Persian until the fourteenth century. Around 1350 a new script called naskh-i ta‘liq emerged. Later shortened to nasta‘liq, it was rapidly adopted for transcribing texts. Its sinuous lines, short vertical strokes, and astonishing sense of rhythm made nasta‘liq particularly well suited for copying Persian verse. By 1430 nasta‘liq was used throughout the Persian-speaking world—from Istanbul to Delhi and from Bukhara to Baghdad.

Several influential calligraphers stood out in the practice and development of nasta ‘liq from the late fourteenth century, when the script first flourished in Iran, until 1600, the apogee of the style. From the second half of the fifteenth century, calligraphers gradually enlarged the scale of the letters, experimented with their placement on the page, and refined their flourishes to create bold displays of a few lines of poetry on a single sheet. By manipulating the size, position, and placement of individual letters and their relationship to each other, calligraphers charged the script with new aesthetic value. The visual essence of nasta‘liq ultimately became as important as the text itself.

Similar to other Islamic scripts, general rules on transcribing nasta‘liq have not been recorded. Instead, aspiring students (shagird) learned the principles of the style from a master (ustad). Only after years of diligent practice and guided by a skilled teacher could a pupil endeavor to become an accomplished calligrapher, who would in turn train his own students. Lineages (silsila) of masters and their pupils were compiled into treatises, a literary genre that flourished in Iran after the sixteenth century.

Four leading master calligraphers dominated the formative period of nasta‘liq (1400–1600).

Mir Ali Tabrizi “from Tabriz” (active circa 1370–1410), the alleged inventor of nasta‘liq

Sultan Ali Mashhadi “from Mashhad” (died 1520), who brought the script to its classical form

Mir Ali Haravi “from Herat” (died circa 1550), who excelled in creating large-scale qit‘as (meaning both fragments of poetry and samples of calligraphy)

Mir Imad al-Hasani from Qazvin (died 1615), the most celebrated calligrapher of nasta‘liq

These masters and their students lent an unparalleled degree of aesthetic refinement to Persian calligraphy over a period of two hundred years. They contributed to the creation and development of nasta‘liq, a script that for more than five centuries has remained a powerful and enduring form of artistic expression in Iran.

Calligraphy Implements

In addition to perfecting their skills, calligraphers were usually responsible for their writing implements and materials. They carefully selected reeds to shape into pens (qalam) and used a sharp knife to trim the tips to the desired angle for different types of strokes. In the fifteenth century, “deviations” in the nasta‘liq style occurred after certain masters trimmed their reed pens in unconventional ways.

Scribes often prepared their own ink based on secret recipes. In 1514 the calligrapher Sultan Ali Mashhadi wrote The Path of Writing (Sirat al-sutur), which includes a short chapter that provides general instructions and lists ingredients, namely, soot (lampblack), gum, alum, and gallnut, to make ink. He also insisted on the importance of preparing the ink himself.

Do not spare labor in this.

Know that otherwise your work has been in vain.

Pens;

Turkey, Ottoman period, 18th–19th century;

Reed and lacquered reed;

Purchase;

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S1991.10 and S1991.12.

Pen knives;

Turkey, Ottoman period, 18th–19th century;

Horn and metal; tinted bone handle with steel blade;

Purchase;

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S1991.7 and F1990.26

Before Nasta‘liq

In the second half of the fourteenth century, scribes developed the nasta‘liq script in order to copy texts composed in Persian. Until then, Persian had been penned by using traditional Arabic scripts, mainly naskh for prose and poetry and ta‘liq for administrative documents. Combining these two styles allegedly formed the root of a new script called naskh-i ta‘liq.

Detail, folio from a Shahnama by Firdawsi in naskh. View full »

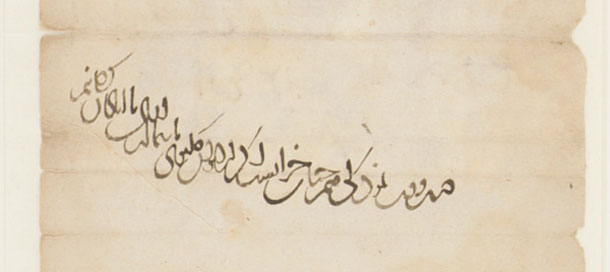

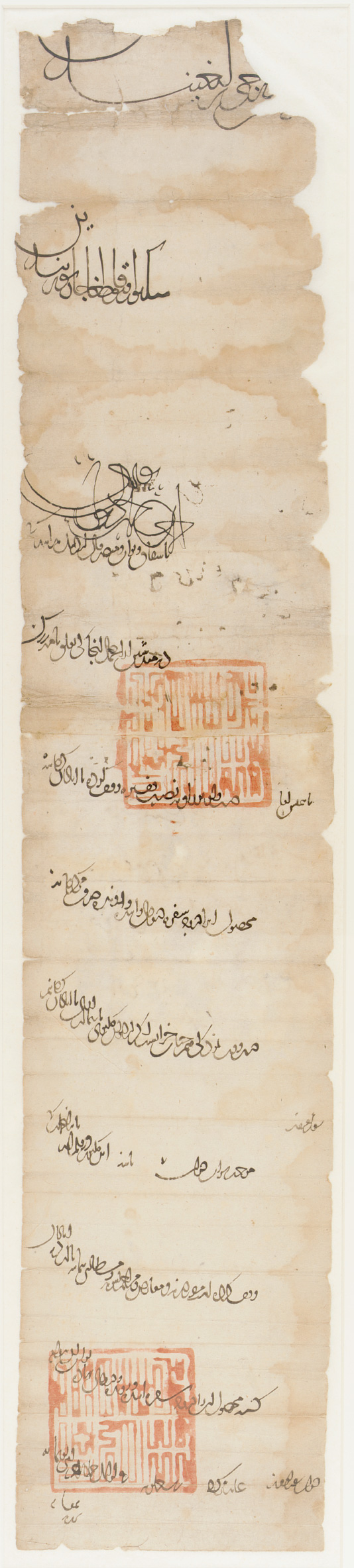

Detail, Farman of the Ilkhan Gaykhatu in ta‘liq. View full »

Khafi and Jali: The Minute and Large Forms of Nasta‘liq

From its inception, scribes used nasta‘liq for the functional purpose of penning full copies of texts in Persian. As such, the script “came into existence” in its minute form (khafi) at the end of the fourteenth century. Throughout the fifteenth century, skillful practitioners further refined “small” nasta‘liq. Jali, the “large” script, developed around 1500, probably under the impulse of Sultan Ali Mashhadi, a master calligrapher active in Herat. Subsequent calligraphers excelled in writing both types of nasta‘liq, but they often mastered either the khafi or the jali script, as noted in later biographies and treatises.

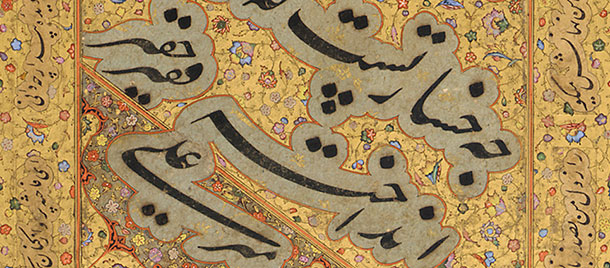

Emphasizing the intrinsic visual quality of the style, jali nasta‘liq was frequently utilized to write two verses on a single sheet. These pages, known as qit‘as (meaning both poetic fragments and calligraphic samples), were later collected, mounted onto dazzling illuminated margins, and gathered into albums.

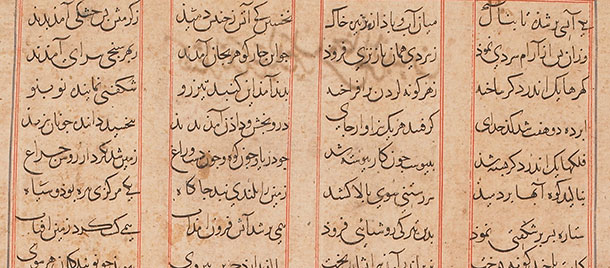

Detail, album folio with five pages of calligraphy in khafi. View full »

Detail, folio from an unidentified album in jali. Learn more »

Scribes favored the cursive script ta‘liq (“hanging”) for writing administrative and diplomatic documents. Taj al-Din Salmani allegedly invented the script around 1400, but ta‘liq was in fact used much earlier, as this decree from the late thirteenth century attests. The first three large lines are in Turkish and the nine subsequent ones are in Persian.

Issued by the Mongol Ilkhanid vizier Sadr al-Din Zanjani to his ruler, the Ilkhan Gaykhatu (reigned 1291–95), this decree, or farman, granting a tax exemption presents an archaic form of the script. Intertwined words and overly curvaceous lines make this Persian text extremely difficult to read for unaccustomed eyes. Slopes, loops, and contrast between the expansion and compression of some letters were later adopted in a subdued manner for nasta‘liq.

It is said Mir Ali Tabrizi developed the new script naskh-i ta‘liq by combining selected features of the naskh and ta‘liq styles.

Probably northwestern Iran, Ilkhanid period, dated 1292 (692 AH)

Ink on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.9

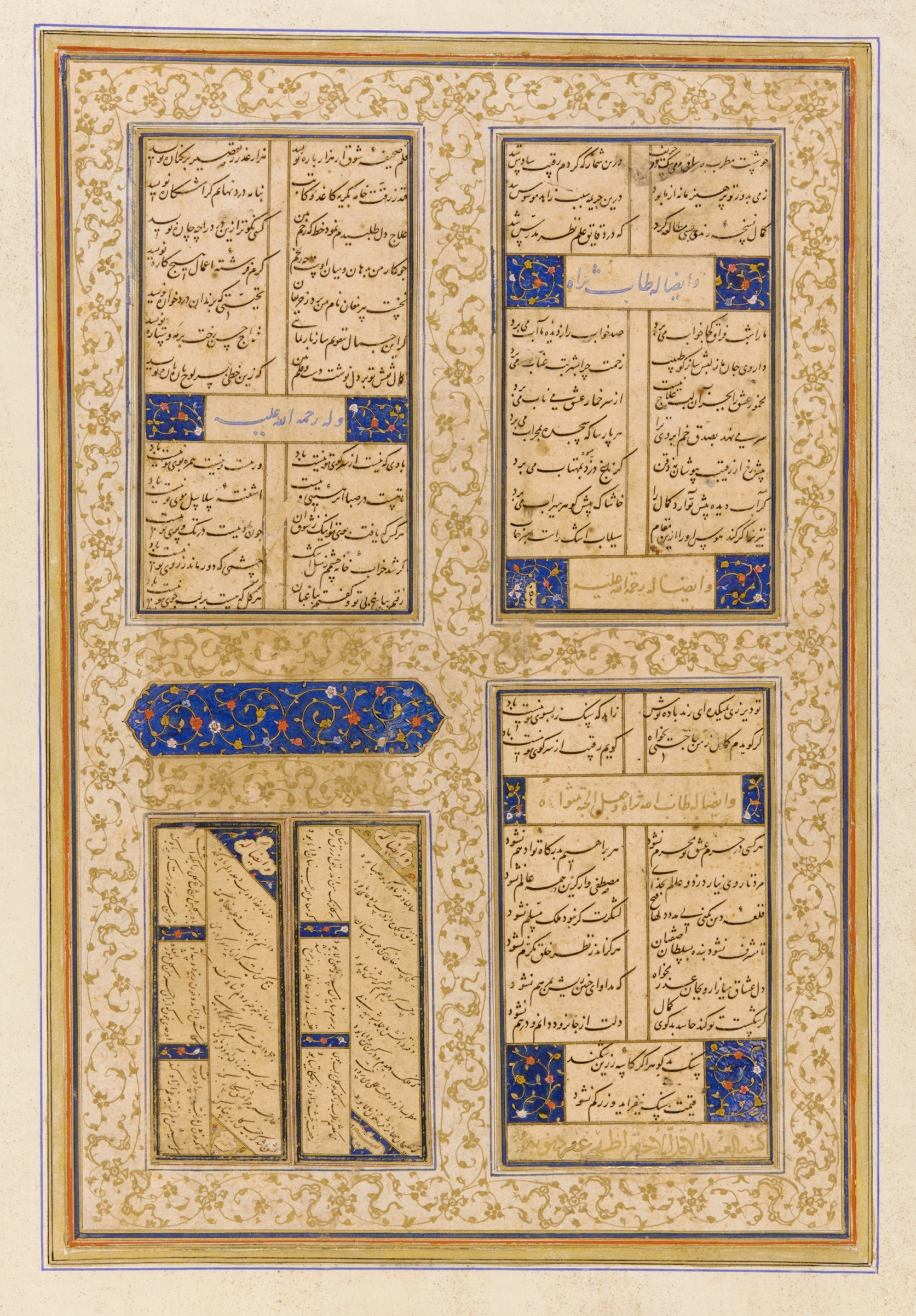

The three text pages on this folio are from the same copy of a Divan (Collection of poetry) by the poet Kamal Khujandi (died 1400). The last page, displayed on the lower right side, ends with the name of the calligrapher, Azhar Tabrizi, written in gold. Two smaller pages in the lower left side were once part of another manuscript that was probably penned by the same calligrapher.

Written in an elegant form of nasta‘liq, these fragments exemplify the minute script (khafi) that was used for copying manuscripts. Each hemistich (half of a verse) occupies one line of each column. Elongated and compressed horizontal strokes smoothly curve, whereas letters, syllables, and words pile up toward the end of each line. The fact that these fragments were later included in an album confirms how works by famous master calligraphers were collected and treasured.

Signed by Azhar Tabrizi

Iran or Central Asia, Timurid period, ca. 1450

Borders: possibly Iran, ca. 1550–1600

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS2002.2.1